Lack of Supply or Demand? What we can learn from South Africa’s experience

By Andrea Taylor and Beth Boyer

December 3, 2021

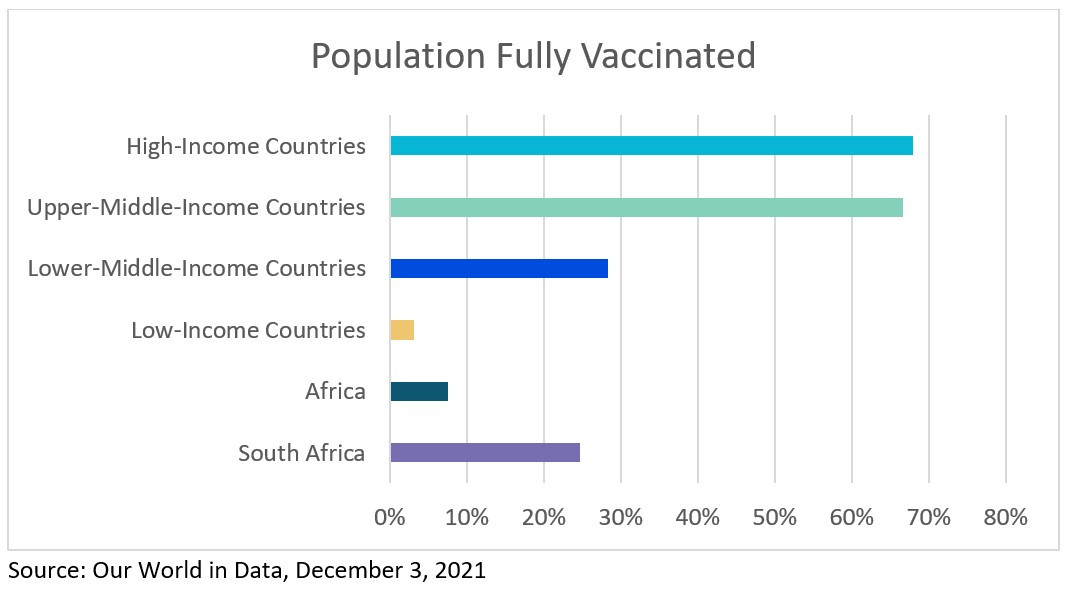

South Africa and a handful of other African nations recently asked vaccine makers to hold off on shipping more COVID-19 vaccines for the time being. Leaders of wealthy countries, accused of hoarding vaccine doses, are using this to make the case that vaccine hesitancy rather than supply is to blame for low vaccination coverage across sub-Saharan Africa. This comes amid the emergence of the Omicron variant, first identified by South Africa’s genome sequencing experts, which has reignited calls to urgently address the inequitable distribution of vaccines.

The demand-not-supply framing overlooks the more complicated reality of vaccination campaigns for countries across Africa. In fact, hesitancy is only part of the problem. According to a survey conducted earlier this year by the University of Johannesburg and the Human Sciences Research Council, 72% of South Africans are willing to get the jab. The factors influencing low demand for the vaccine are more complex and challenging than they appear on the surface.

There are at least two important reasons why it is critical to take a nuanced view of what is happening in South Africa:

First, successful mass vaccination requires more than just doses in hand. Even wealthy countries such as the United States had early challenges rolling out vaccine campaigns due to storage requirements, logistics, and health workforce needs. That is why in our latest report – and our previous open letters to US and G7 leaders – COVID GAP has been calling on wealthy nations to provide not only more doses, but also much needed support for distribution, delivery, and demand generation.

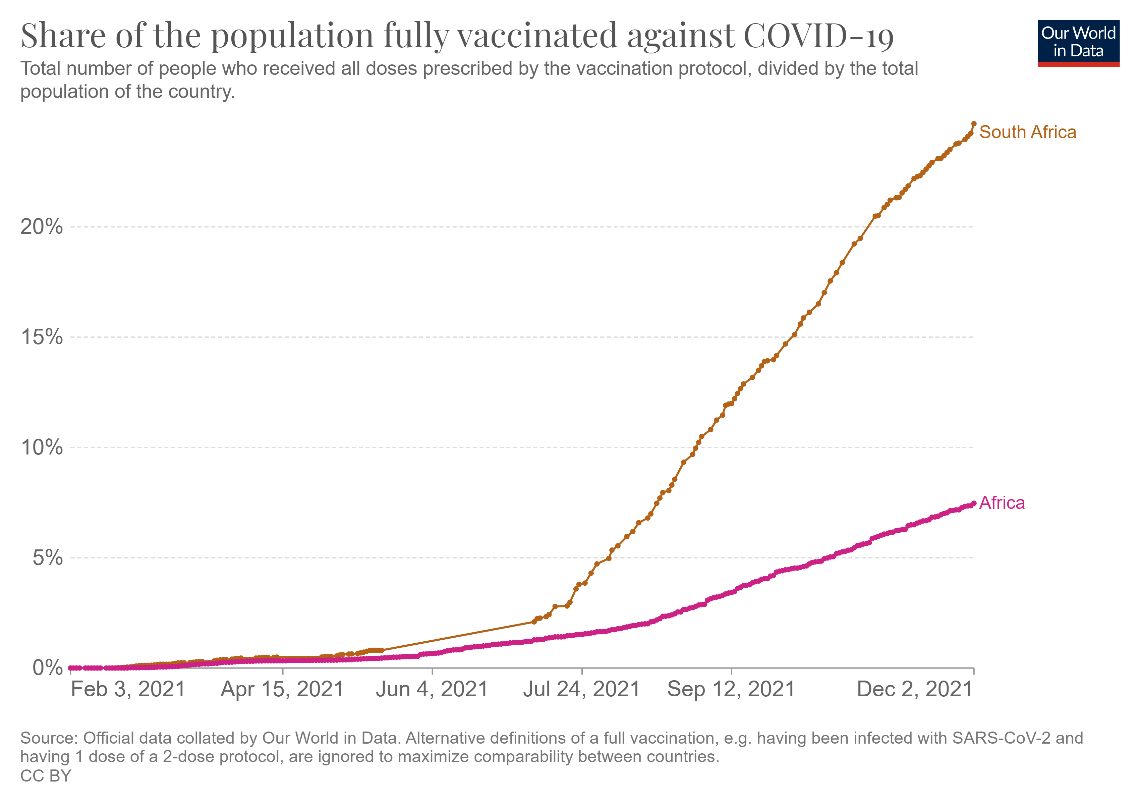

Second, South Africa is in some ways an outlier on the African continent. It is upper-middle income, is procuring doses through bilateral deals with vaccine makers, has vaccine manufacturing firms with fill-finish contracts for approved vaccines, and has fully vaccinated 24% of its total population – among the highest coverage on the continent. As such, South Africa is one of the few countries in Africa that has had enough incoming supply to test absorption capacity and demand. Its experience provides insight into what other countries in the region may soon experience.

The issues limiting vaccination rates in South Africa and many neighboring countries can be summed up by coordination, cold chain, capacity, and communication.

COORDINATION. There is insufficient supply of vaccine doses needed to reach the 40% coverage target in sub-Saharan Africa. An additional 683 million doses are still needed. But the flow of supply matters as well. Many countries go months without any new supply and then are suddenly inundated with millions of doses, which overwhelms the vaccine delivery infrastructure. Deliveries need to be predictable and consistent, so that health systems can plan ahead and use their stretched resources efficiently. The African Vaccine Acquisition Trust (AVAT) and Gavi recently requested that donations come with 4 weeks of advance warning and a minimum of 10 weeks remaining before expiration.

COLD CHAIN. While South Africa does have significant cold-chain (and ultra-cold-chain) storage and supply chain capacity, even this can be pushed to the brink by the feast-or-famine nature of vaccine deliveries to the country. For many other countries in Africa, particularly outside of large cities, cold chain storage will be a significant rate limiter to absorption capacity as supply begins to increase.

CAPACITY. Overstretched health systems in many sub-Saharan African countries face capacity challenges with such a large vaccination effort. Government leaders report that lack of trained vaccinators is a key bottleneck. Other limiters reported include inadequate data systems and limited vaccination sites, especially in more rural regions.

COMMUNICATION. Just as in the US and many countries in Europe, misinformation and rumors are being spread about the vaccines, creating fear and hesitancy. This must be addressed head-on with public communication campaigns to fight misinformation. In many sub-Saharan African countries there is also the added issue of historic mistrust of Western medicine and products. Governments should engage with trusted community leaders to help address hesitancy and misinformation. Additionally, greater public awareness and education on the risks of COVID-19 and importance of vaccination can reduce apathy, motivating those who are willing to get the vaccine but are put off by inconveniences.

Going back to the question at hand: is the challenge in sub-Saharan Africa a lack of supply or demand? The answer is both. As a global community, we must address bottlenecks in both supply and demand generation to increase vaccination coverage everywhere to slow transmission. Redistribution of existing supply is important, but it is not as simple as shipping more doses. Supply must come in a manageable and predictable flow and be coupled with support to address other bottlenecks, including cold chain storage, vaccinator capacity, and vaccine hesitancy.

To do this effectively, we need more and better data on what is slowing down vaccination coverage as nearly 80 countries are at risk of missing the 40% target by yearend and may struggle to meet the 70% target by mid-2022. COVID GAP is partnering with the Africa CDC and WHO to convene experts and leaders from low- and middle-income countries later this month, to clarify bottlenecks to vaccination at the country level and prioritize recommendations to urgently address these issues. We will continue to work with our country partners to build evidence that defines the scope of the problem and drives relevant and effective action.